Introduction

In an increasingly integrated society, heterogeneity of worldview is growing in nearly all advanced economies. According to the Center for Immigration Studies, the foreign-born population in the United States hit 42.4 million, or 13.3 percent, of the total US population in 2014. With easy access to the Internet, ideas can spread rapidly allowing scholars to virtually coordinate research with labs across continents and religious missionaries to proselytize tens of thousands in all corners of the world. The previous literature on international economic development asserts that ethnic and religious fractionalization can reduce support for public goods, generate communication costs, and induce divisiveness. Other studies on diversity note that heterogeneity also widens the pool of knowledge and variety of preference sets, increasing the breadth of goods, services, and ideas available for consumption and production. To contribute to the literature on the economic effects of diversity, the objective of this paper is to examine the relationship between worldview diversity and entrepreneurial activity in US metropolitan areas.

I make three contributions in this paper. First, I construct and assess a new index of worldview diversity, called the Diversity of Perspectives Index (DPI), which defines each combination of nationality, gender, field of study, and occupation as a unique identity. It differs from previous studies analyzing political and economic effects of diversity, which rely on either ethnicity, language, or religion to define cultural identity. Unlike these traditional measures of diversity, the DPI better captures the integration and assimilation of various cultures. Further, the DPI places equivalent weights on the value of ethnic, linguistic, gender, academic, and occupational diversity. Second, I investigate the relationship between this newly constructed index, the DPI, and startup formation using an OLS linear regression model. Last, I incorporate previously used diversity indices into the model to test the strength of the DPI as an indicator of startup activity relative to simpler measures of cultural diversity. The regression results of DPI on new firms per 10000 capita reveal a statistically significant relationship. The significance of the DPI’s effect on startup formation withstands the addition of other indices to the model.

Diversity at the Firm Level:

A diverse environment contains a greater number of perspectives than a more homogenous society. With a greater variety of approaches to solving problems, there is an increased likelihood of an optimal solution as well as an increased likelihood of conflicting opinions. Both outcomes increase incentives for the founding of new firms whether the motive is to exploit a business opportunity or to challenge an established business with a conflicting and unique idea. Previous literature has studied this relationship and the mechanisms facilitating the relationship between diversity and productivity on both the firm and societal levels.

At the firm level, Hong and Page (2001) decompose the effect of heterogeneity in problem solving behavior by identifying (1) how people perceive problems internally, their “perspectives”, and (2) how they go about solving them, their “heuristics”. They show theoretically that all else equal, e.g. absence of incentive and communication problems, less-skilled groups with diverse perspectives or heuristics can outperform relatively more skilled groups that are homogenous. The contention that greater variety in heuristics and perspectives leads to better outcomes may seem noncontroversial. Nevertheless, the formal model contributes a useful tool for economists to understand the mechanisms driving productivity in the presence of diversity.

In a separate study, Hong and Page (2004) extend the cognitive benefits of a diverse environment to show that even randomness, given a diverse pool of intelligent people, can assemble a group that outperforms a group of top scorers. They provide an illustrative example in which an organization administers a test to 1000 individuals with the aim of hiring a team to solve a difficult problem. Their conclusion asserts a randomly selected group can outperform top performers as long as certain criteria are met. For example, if the pool of individuals is large enough, the group of top performers is likely to be more homogenous since the test funnels like-minded individuals to the top. However, if the group is too large, the group of top scorers may itself become diverse and perform relatively better. Therefore, the advantage of random selection over performance-based selection faces decreasing marginal returns commensurate to the size of the group. When considering the real-world applicability of this study’s theoretical findings, one key limitation is the absence of communication costs that would surely arise with teams whose members speak different languages.

By observing firm-level impacts of cultural heterogeneity as measured by linguistic diversity, Edward Lazear (1999) addresses this concern. In his model, there is a possibility of individuals speaking different languages. According to his findings, firms that combine cultures incur costs because some team members must be bilingual or bicultural. However, cross-cultural interactions can increase overall productivity through increase in variety of skills available and strategic complementarities from disparate information sets. Given a profit-maximizing objective and a production unit, there exists an optimal level of heterogeneity where the benefits of diversity outweigh its communication costs.

Jehn, Northcraft, and Neale (1999) distinguish several types of diversity, such as social category diversity and value diversity. Social category diversity is defined by explicit differences in social category membership, namely race, gender, and ethnicity. Value diversity occurs when members of a workgroup differ in terms of what they think the group’s real task, goal, target, or mission should be. The study finds that social category diversity positively influences group member morale, while value diversity decreases satisfaction, intent to remain, and commitment to the group.

These studies show that diversity benefits groups by widening the range of viewpoints, but can also introduce costs. However, the merits of diversity can be codependent on the costs themselves. Through debate and challenges of each others’ assumptions, the adversarial environment gives rise to optimal solutions. So the effect of diversity and whether its benefits can be fully realized largely depends on the group’s ability cooperate. At the firm level, it is possible that a united profit-maximizing orientation can mitigate the harmful potential of diversity.

Political and Social Effects of Diversity:

On a societal level, a greater number of individuals as well as a greater number of distinct ideological viewpoints can increase both coordination costs as well as the potential for conflict. This suggests that the benefits of diversity within groups at the societal level rise with the strength of political and social infrastructure in their ability to reduce conflict.

Accordingly, when the number of people in a group is much larger, i.e. entire cities, the costs of diversity can become much more difficult to manage. For example, heterogeneity can induce costs from conflicting preference sets, communication costs, and social capital costs such as outright racism and prejudice (Alesina, Bar, and Easterly). One tangible implication of such costs is a sub-optimal provision of private and public goods. However, strong political infrastructure can nullify the harmful effects of fractionalization.

Economists, sociologists, and political scientists have contributed vast literature on the impact of diversity on public goods. According to Williams and O’Reilly (1998), the social characterization view posits that individual perspectives are defined by one’s similarities and differences and a characterization of insiders and outsiders. Unless there are measures in place to facilitate coordination, empirical evidence suggests that diversity is more likely to harm group performance. Social capital and trust is greater amongst insiders, implying greater conflict between heterogeneous groups (Fearon and Laitin 1996). Alesina, Bar and Easterly (1999) shows an adverse relationship between the extent of ethnic fragmentation in an economy and level of spending on public goods. Easterly and Levine (1997) find that the underperformance of African nations is attributable to high levels of ethnic fractionalization, resulting in weaker numbers of telephones, percentage of roads paved, efficiency of the electricity network and years of schooling.

The effect of diversity on developing countries can also depend on the magnitude of heterogeneity. Nikolova (2013) finds that the relationship between diversity and entrepreneurship will follow an inverted U-shaped pattern. When the level of cultural heterogeneity is low to medium, its benefits will outweigh the costs, since enforcing inter-group collaboration is easy. However, as the number of religious and linguistic groups increases, the costs of establishing complex institutions outweigh the advantages involving social networks.

Recent literature has found that strong political and economic institutions, such as protection of property, free markets, the rule of law, and a free media, can mitigate and even nullify the harm caused by ethnic fractionalization. Leeson (2005) explains that the legacy of colonization in Africa maintain weak institutions that disrupt trade, hindering economic growth. The negative effect of fractionalization is secondary to the colonial institutions of property law and religious policy. Alesina and La Ferrara (2005) find rich democratic societies work well with diversity in terms of productivity and growth, particularly in the United States.

Diversity and Economic Growth:

Previous research on the role of diversity on productivity has primarily relied on differences in ethnicity and language to measure diversity. Ottaviano (2005) finds a positive effect of linguistic diversity on wages across metropolitan statistical areas in the US. His research indicates that cities with richer linguistic diversity enjoy systematically higher wages and employment density of US-born workers. Audretsch and Feldman (2004) find that diversity across complementary economic activities is more conducive to innovative output than is the specialization. Building on this result, Audretsch (2009) adds that cultural diversity of people and its effect on the level of knowledge form an ideal ecosystem for technology-oriented start-ups.

Florida (2001, 2002) takes a unique approach by creating the bohemian index, a measure of the bohemian concentration for MSAs with the 50 greatest populations. Florida defines a bohemian as an individual practicing an artistic occupation, such as author, designer, musician, composer, actor, painter, sculptor, performer, or dancer. The theoretical relationship between bohemia and entrepreneurship relies on the role of “bohemian” diversity in nurturing cultural and creative milieus. Florida suggests that the presence of alternative communities supports an environment that welcomes innovation and creativity. The results find a positive and significant relationship between the bohemian index and concentrations of high-technology industry. Such ecosystems are more likely to be tolerant of unique ideas and consequently more likely to attract creative and entrepreneurial leaders. However, Florida does not explicitly state a mechanistic relationship between bohemian concentrations and concentrations of start-ups.

By definition, a region with many different worldviews contains a wider variety of preference sets than a homogenously oriented society. But in addition to the relatively greater number of viewpoints, diversity itself also expands the breadth of goods and services. Heterogeneity multiplies possible combinations of ideas and increases the likelihood of creative destruction and innovation. It increases opportunities for ideas to merge, for the study of interdisciplinary fields, and for clashing perspectives to challenge each other’s assumptions. Consequently, new sets of skills become required to produce the new goods and services.

Studying the merging of cultures through trade, Cowen (2002) argues that globalization enhances the range of individual choice and expands the menu of choices available to consumers. It is not merely that the multitude of backgrounds expands individual choices; Cowen suggests that the infusion of cultures inevitably spurs innovation and gives rise to hybrids and new genres. Audretsch and Feldman (1994) studied sectoral diversity and found that specialization of economic activity does not promote innovative output; rather, it is the diversity across complementary economic activities that is more conducive to innovation than is specialization.

DATA DESCRIPTION:

- Dependent Variables

The Business Dynamics Statistics (BDS) provides annual measures of business dynamics such as firm openings, firm closings, job creation, and job destruction. The Census Bureau maintains the BDS using data provided from the Business Register, payroll taxes from the Internal Revenue Service, and Annual Survey of Manufacturers. The BDS provides the most comprehensive measure of startup formation and also provides specific counts of firms of age zero to one with nine or fewer employees. In order that coefficients of regression results can be easier to interpret, I use new firms per 10,000 capita to represent the level of startup formation.

One disadvantage of the BDS is that the data does not provide detailed industry information at the MSA level. The inability to filter by industrial sector makes it difficult to assess the level of innovation in cities. In order to more directly address the relationship between heterogeneity and innovation, I will also be using a measure of patents per capita as provided by the United States Patent and Trademarke Office (USPTO).

- Explanatory Variables

The ethnic index of fractionalization is the most common method of measuring cultural diversity. Using a person’s place of birth to represent his or her distinct cultural identity, the index ranks regions based on the degree of heterogeneity. The index is equal to zero if the region is completely homogenous and approaches one as diversity increases.

sim is region i’s population share belonging to nationality m and Mi is the number of different nationalities actually present in region i. As Audretsch (2010) explains, this approach to measuring cultural diversity has an unpleasant characteristic because it weights the highest share (e.g. Those born in America) disproportionately high.

In order to account for the distribution of different nationalities within the foreign population, Audretsch suggests the use of an entropy index:, also known as the Theil index of cultural diversity:

For each region i, the index takes the sum of the product of the shares and log shares of each group in the total population. If all ethnicities are of equal size in a region, the index is equal to ln(1) = 0. As diversity increases, the index value approaches ln(Mi).

There are also variations of the ethnic index of fractionalization that apply the same arithmetic using a different definition of cultural identity. For example, the Linguistic Diversity Index (LDI) is an alternate method of measuring diversity and uses language as a proxy for cultural identity. One key benefit of the LDI is that it can capture cultural identity beyond first-generation immigrants. In contrast, a foreign country of origin is unique to the first generation immigrant. Studies have also used religion to classify cultural identities. Nikolova (2015), for example, uses religious diversity to capture the effect of religious heterogeneity in new firm startups in Central and Eastern Europe.

Ethnic, linguistic, and religious diversity are reasonable measures of cultural diversity. Within the context of the theoretical relationship between diversity and productivity, however, there is room for improvement. The primary benefit of cultural diversity is not simply the presence of different ethnic flavors, but the presence of divergent perspectives, of which ethnic identity is just one. The theoretical relationship between cultural diversity and productivity is also applicable to occupational diversity and educational diversity. In both cases, the fundamental theme of an economic benefit from the presence of varying world views persists. Cultural diversity is a good indication of heterogeneity of perspectives, but cultural diversity within the context of education and occupation provides a stronger measure. To attempt to improve the measurement of heterogeneity, I formulated a new index called the Diversity of Perspectives Index. The index is calculated using the entropy index method:

The new index is similar to the Thiel index; however, m no longer represents just a nationality; rather, each m is a unique combination of gender, nationality, occupation, and area of study. Whereas CDI and LDI would represent a person born in Canada as one identity, the DPI would define a female lawyer born in Canada with a degree in Engineering as a unique identity. In this way, the DPI adds to the traditional calculation of diversity as a measure of the variety of nationalities. The DPI incorporates the mixture and assimilation of different ethnicities and genders.

A correlation matrix of both independent and dependent variables reveals that the CDI, LDI, and Theil index are nearly perfectly correlated to each other. The correlation between the DPI and each of the three alternative measures of diversity is relatively more moderate. With regard to the dependent variables, firms per capita (FPC) and patents per capita (PPC), there is a weak relationship.

IDENTIFICATION STRATEGY:

I estimate two sets of Ordinary Least Squares regressions for each measure of entrepreneurial activity: new firms per capita (FPC) and patents per capita (PPC). The first set tests the relationship between entrepreneurial activity and the Diversity of Perspectives Index (DPI). The second set estimates a multiple linear regression model with both traditional measures of diversity as well as the DPI. The total group of indices will consist of the Cultural Diversity Index, the Linguistic Diversity Index, the Thiel Index, and Diversity of Perspectives Index.

First, I estimate the relationship between the DPI and startup formation. The econometric model has the basic form:

where is the level of new firm formation in region i. A new firm is defined as a business aged between 0 to 1 years and consisting of fewer than 9 employees.

is the diversity measure in region i. The error term,

, captures the effect of an incorrect functional form, the effects of omitted variables, and the measurement errors.

Second, I estimate a model with the inclusion of other indices:

where for region i, CDI is the cultural diversity index, LDI is the linguistic diversity index and T is the Thiel Index.

RESULTS:

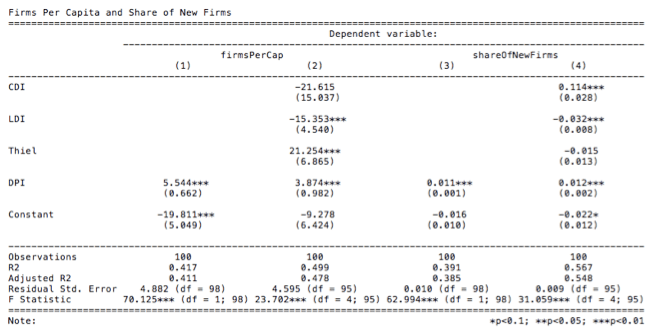

Table 1 shows that a higher level of diversity leads to a greater number of new firm formations. Even when CDI, LDI, and Thiel indices are added to the model, the effect of the DPI index on new firm formation remains significant. Column 1 shows that a 1-point increase in the DPI increases the number of new startups per 10,000 capita by 5.544. Similarly, Column 3 shows that a 1-point increase in the DPI leads to an increase of 1.1% share of startups relative to firms of all ages. In both cases, I can reject the null hypothesis that DPI has no significant effect on the startup rate.

Column 2 shows that the coefficient on diversity of perspectives remains positive and significant at the 1 percent level even with the incorporation of CDI, LDI, and Thiel indices as independent variables. Since CDI, LDI, and Thiel indices are strongly correlated to each other, multicollinearity issues between the three traditional measures of cultural diversity reduce the precision of the regression and are likely causes of the negative coefficients for CDI and LDI. However, the three traditional measures of diversity are not strongly correlated to the DPI and do not affect the significance of the coefficient for DPI. The implication is that the diversity of perspectives index contributes to startup formation even when controlling for the effects of single dimensional indices that measure ethnic and linguistic diversity.

In Column 4, the DPI survives the same test using the share of new firms as the independent variable, instead of firms per capita. Again, adding CDI, LDI, and Thiel indices to the model, the coefficient for the DPI remains significant at one percent. There still remain multicollinearity issues between CDI, LDI, and Thiel, which are likely causes of the negative coefficients for LDI and Thiel index. For both firms per capita and share of new firms, the DPI is strongly correlated to startup formation rate in spite of the addition of traditional diversity measures to the model.

TABLE 1:

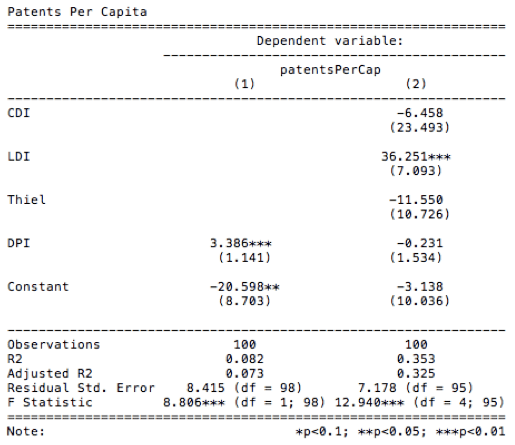

Table 2 shows that a higher DPI value leads to a greater number of patents per 10,000 capita. In Column 1, the coefficient is positive and significant at the 1-percent level and a 1-point increase in the DPI is associated with an increase of 3.386 patents. However, when the alternative measures of diversity are incorporated into the model in Column 2, the coefficient for DPI is negative and no longer significant. Instead, the coefficient for LDI is very large and significant. Due to multicollinearity issues, however, I cannot conclude that the linguistic diversity is a strong indicator of patents per capita. Additional tests are required to determine the strength of the relationship between linguistic diversity and patents.

Table 2:

Conclusion:

Using a newly constructed measure of diversity, the Diversity of Perspectives Index, this paper finds that an increase in diversity leads to growth in the creation of startups. The results are consistent even with the addition of traditional measures of diversity, such as the cultural diversity index, linguistic diversity index, and the Thiel index. The implication is that greater variety in the number of ethnicities working in various professions with different educational backgrounds leads to a higher propensity to start new firms.

One key limitation of this study is the restricted availability of characteristics that can be used to determine a “perspective”. The diversity of perspectives index was created using the One Percent Public Use Microdata Sample of the 2014 U.S. Census. For this reason, the index was limited to nationality, gender, field of study, and occupation. If the data were available, the inclusion of other identity characteristics such as political affiliation and religious practice into the index calculation could provide a stronger or perhaps weaker relationship to startup formation.